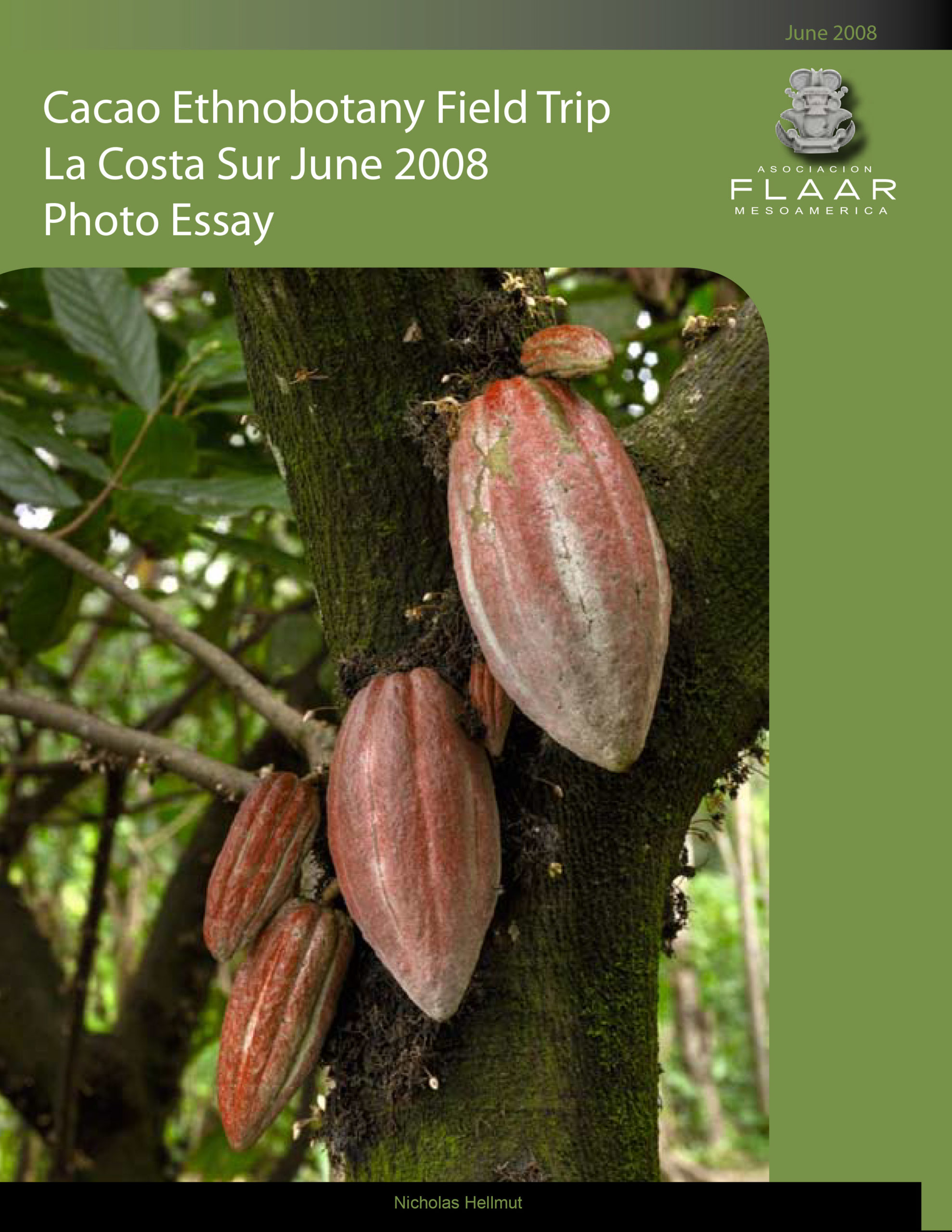

Parmentiera aculeata a fruit missing from lists of Maya foods

Parmentiera aculeata is one of the edible indigenous fruit trees that has been totally forgotten by Mayanists. The colonial chronicles mention the fruit of this tree as one of the foods grown in the yards or fence rows of houses, and were part of the staple diet of some villages where the tree flourished. Similar to cacao, the fruit can be eaten raw or cooked in different ways. (Calixto, 2005)

Caiba, cuajilote, Parmentiera aculeata fruit elongated, Photo by Nicholas Hellmuth.

Caiba, cuajilote, Parmentiera aculeata fruit oblong, the fruits can be of different shapes, Photo by Nicholas Hellmuth.

The cuajilote is often discussed on web pages about fruits of Veracruz, Morelos, and Oaxaca Mexico, including the Jardín Botánico de Cuernavaca, Morelos, México and program of Medicina Tradicional. Escuela de Enfermería Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos. Plus there is a short thesis by Pedro Angon Galvan (Oaxaca). The comments on the medicinal usage are from various sources including the above.

The applications are clearly listed: used as a laxative and diuretic in various parts of central and southern regions. It is also recommended to treat kidney ailments and their treatment includes fruit, bark, flowers and roots, which are being boiled and eaten as a tea. In other cases such as kidney and urinary tract infections, is effective grinding and eating fruit extract or roast and eat it. Besides cooking the flower, root or fruit, is a good diuretic. It is also used for other diseases such as asthma, flu and cough, the flowers are boiled with and sweeten to drink warm for two weeks. (Hipernatural.com).

This little-studied fruit has uses that could be potential, if not to establish large-scale commercial plantations, at least to spread their properties and potential benefits: it is the preparation of jams from the caiba, because although it has fleshy fruit it has the disadvantage of being rather fibrous. (Calixto, 2005)

Caiba, cuajilote, Parmentiera aculeata flower, Photo by Nicholas Hellmuth.

In some regions of Guatemala is used as feed for pigs and cattle, but this is occasionally practiced by some producers as a free resource.

Its a tree that grows up to twelve meters thick high, with glossy leaves of bright green. The stalk has occasional sharp spines. The flowers of this species grow from the trunk. So the fruit hangs from the trunk and main branches. Because the fruit is relatively soft, consumption is generally limited to the areas where cuajilote thrives. (Parker, 2008)

The manner in which the flower grows and hence where the fruit issues from, is very similar to its tree relatives the morro and jicaro.

Caiba, cuajilote, Parmentiera aculeate flower and fruit, Photo by Nicholas Hellmuth.

Some sources say the fruit can be eaten raw. Others say the fruit is cooked before being eaten, often stuffed with meat. In Aguacatan the ripe fruit is used to prepare sweets. It is reportedly eaten by pigs when available (Parker, 2008).

The tree is found in abundance on the dry hills between El Rancho and Salama, less frequently in other dry regions. Although it is widely cultivated in Guatemala, the trees are not very numerous since the fruit is generally not highly esteemed (Parker, 2008).

I (Nicholas) have found and photographed this tree and its fruit in

- Jardin Botanico, Guatemala City

- Monterrico, near the Pacific Ocean

- Sayaxche, El Peten

- Remate, El Peten

And there may have been some examples in the Rabinal or Salama area (but my mind is overloaded by all the other plants we found and photographed in those seasonally dry areas).

I had never seen or heard of this plant ever before 2009. In past years, for monkeys carrying fruits on Tepeu 1 and Tepeu 2 vases I avoided immediately stating they were cacao since frankly many of the fruits were of rather lopsided shape. But I would have tended to have accepted most identifications of cacao on incensarios and figurines until several years ago when so many fruits in Mayan art were listed as cacao that I felt it would be good to document these identifications, fruit by fruit. By 2010-2011 I had enough evidence of all the faux-cacao and I prepared the lectures at Tulane and in San Salvador.

In 2009 botanist Mirtha Cano mentioned it occurring in a hotel near Remate, El Peten. Then in 2011 I found and photographed this tree in several more locations, and included Parmentiera edulis in several lectures on Maya iconography.

I have never noticed this plant in any list by archaeologists of Maya fruit plants (though I am sure it is present, since the tree is not that scarce).

Caiba, cuajilote, Parmentiera aculeata fruits growing from the trunk at Sayaxche, Peten, Guatemala. Photo by Nicholas Hellmuth.

Scientific name; common name of Mayan ethnobotanical edible fruit

Parmentiera edulis D.C. is the scientific name. Synonym is Parmentiera aculeata (Kunth) Seem. This is the designation given by Ana Lucrecia de MacVean (2003:34). But about half the web sites nowadays call it Parmentiera edulis.

Cuajilote is the most common local name, both in Mexico and Guatemala and evidently also in Costa Rica. Like most local plants it has a different name in each local cultural area; so I prefer to stick with the most common international name, cuajilote.

The name is also spelled Guajilote.

Also realize that most Spanish common names for plants are imprecise: most words are used for many diverse species that have no relationship to each other. So I avoid using the word caiba, and I prefer to stay with cuajilote.

Be careful with common names, as a UNAM web site (Atlas de las Plantas de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana) lists Pseudosmodingium perniciosum (Kunth) Engelm, Anacardiaceae under the local name cuajilote. The cuajilote we study in Guatemala is generally named Parmentiera edulis, and is of the Bignoniaceae family.

Caiba, cuajilote, Parmentiera aculeata tree notice the fruits growing from the trunk similar to cacao pods that also grows from the trunk. Photo by Nicholas Hellmuth, jardin botanico, Ciudad de Guatemala, Guatemala.

Flowers and fruits directly from the trunk: cauliflory

Theobroma cacao is the best known cauliflorous species. Theobroma bicolor (pataxte) is not as well known since it fruits high high up on the upper portion of the trunk, whereas common cacao fruits from the trunk at ground level up and down the entire trunk (so easily at eye level).

Further reading on cuajilote, Parmentiera edulis or Parmentiera aculeata

Jardín Botánico de Cuernavaca, Morelos, México

Medicina Tradicional. Escuela de Enfermería Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos

ANGON GALVAN, Pedro

2006 Caracterizacion parcial del fruto de Parmentiera edulis. Thesis (Ingeniero en Alimentos), Universidad Technologia de la Mixteca. Oaxaca. 52 pages.

I could not find cuajilote mentioned in Plantas Utiles de Solola, by Ana Lucrecia de MacVean, suggesting that Lake Atitlan area is not an area for this tree. Her book on utilitarian plants of the Peten has been out of print and we can't even find a copy used in Guatemala. But from the scanned copy as a PDF I can look to see what is included: cuajilote is mentioned (but of course not the iconographic aspects). Frankly I find cuajilote a fascinating species and well worth further study (far more than it being a faux-cacao).

To remind outselves how “forgotten” and overlooked cuajilote really is, if you look at the 505 page monograph, Fruits of Warm Climates, by Julia F. Morton, I was not able to find any cuajilote, caiba or Parmentiera species in her index. So here is a literal bible of tropical fruits and cuajilote is totally missing.

One of the long-range goals of FLAAR is to suggest that indigenous plants can resolve many of the health and food shortages of the countries of Mesoamerica. The problem of course is that there are no multi-national food companies making profit from healthy local fruits! So it would sure help to have grants to help the local people know of all the nutricious foods which they can grow literally in their backyards.

I discuss the faux-cacao aspect in our related web site, www.maya-archaeology.org.

Most recently updated April 2, 2012.

First posted August 17, 2011.