General situation of Pachira aquatica in Mesoamerica

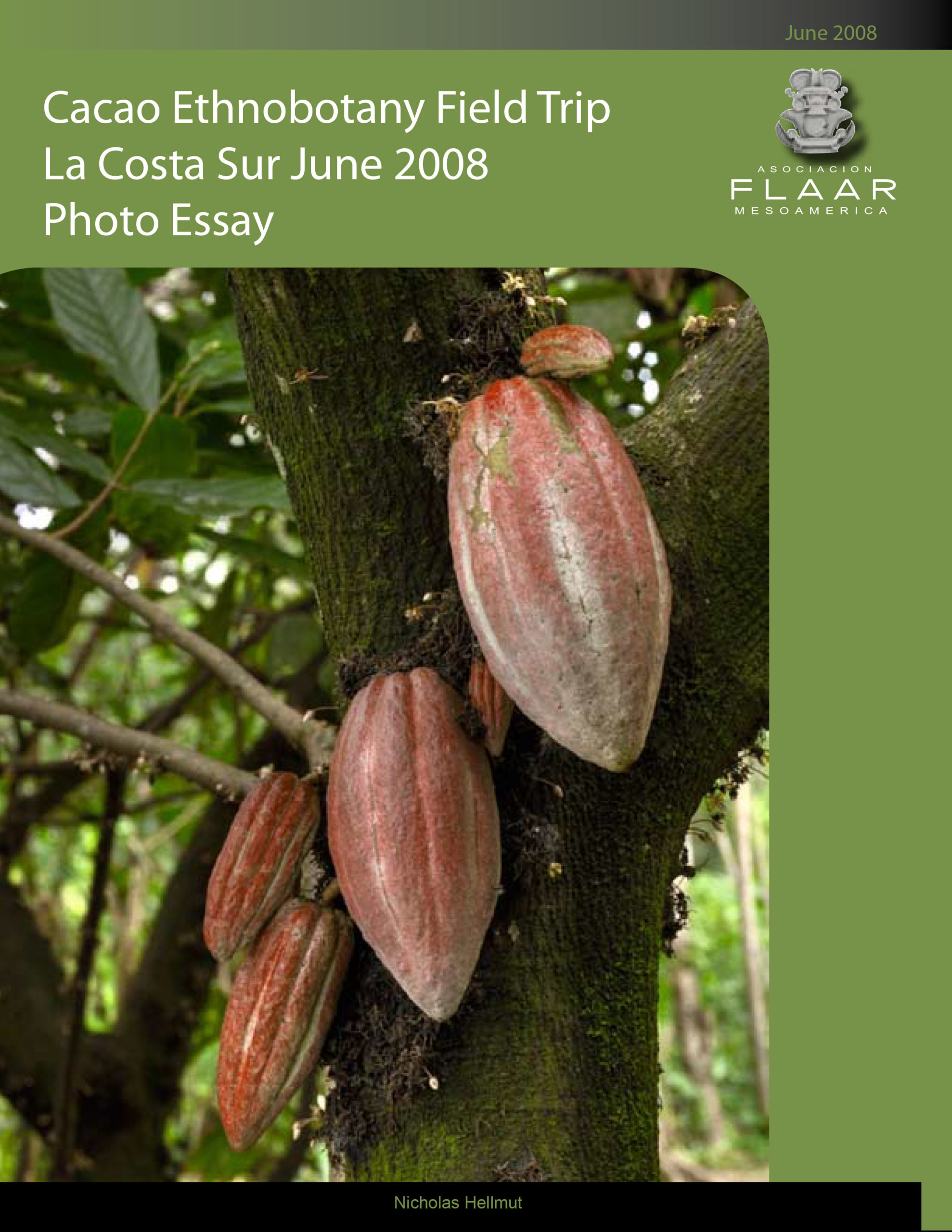

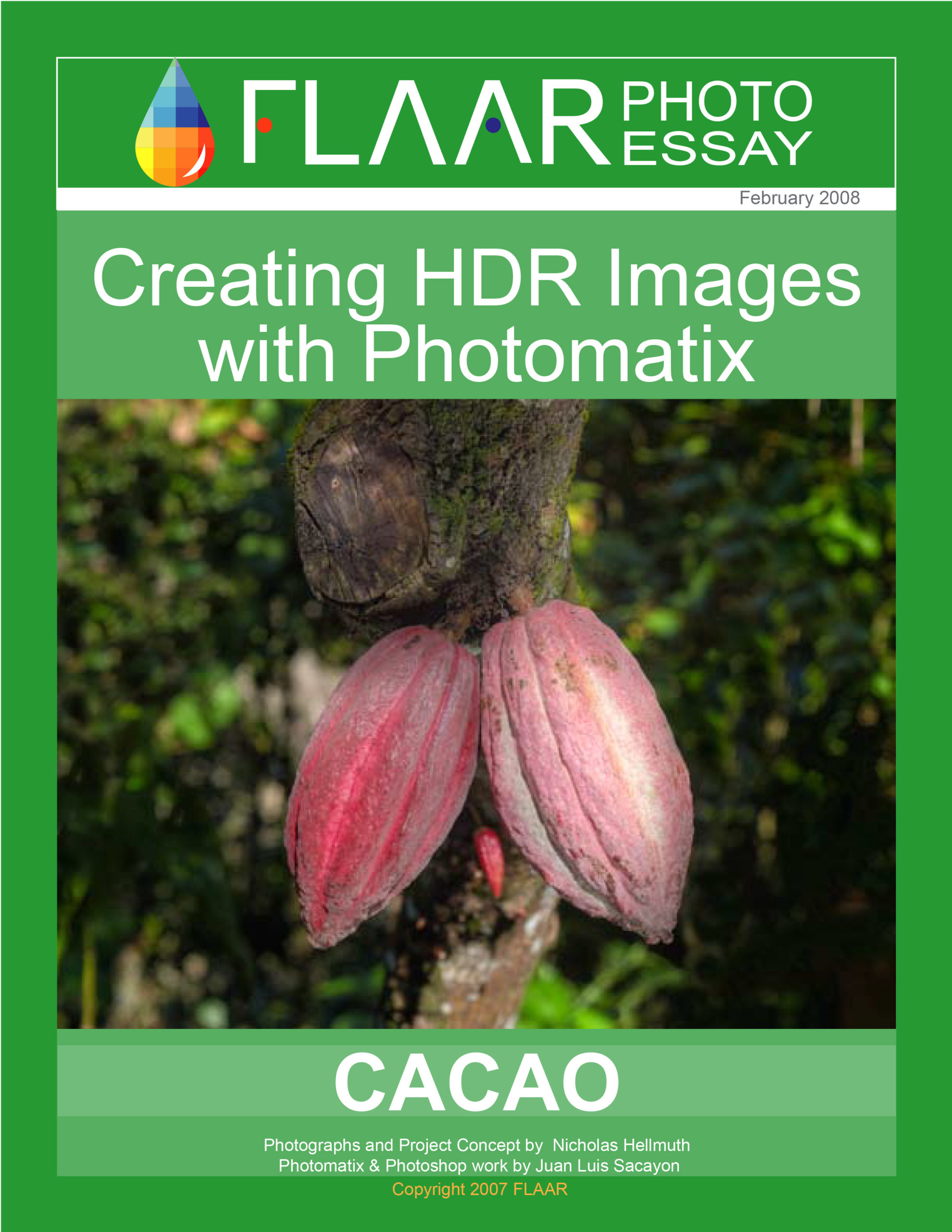

Pachira aquatica has a remarkable flower and a huge fruit. The fruit looks like a giant zapote and for this reason is called zapoton (also spelled sapoton, as zapote is also spelled sapote). The outside color and fuzz of the zapoton reminds you of a zapote also. But inside it is totally different: zapote has one long dark brown seed; zapoton has a mass of seeds that together look like a segmented brain.

The tree is a member of the Bombacaceae, the Kapok-tree Family. You could tell that yourself even if not a botanist since the leaves are similar to Ceiba leaves. The fruit is, however, ten times larger, and there are fewer spines on the trunk. Nonetheless, this tree grows near the water and I bet crocodiles and caimans knew that animals would come feed on the fruits when they dropped into the water or onto the shore.

Ironically the best known Ceiba, Ceiba pentandra, has flowers which, to a non-botanist are totally different in size, shape, and colors than Pachira aquatica. But the flowers of Ceiba schottii (Yucatan, not listed for Guatemala), Ceiba aesculifolia (most of Mesoamerica) and especially of Pseudobombax ellipticum, are visually quite similar to the flowers of Pachira aquatica.

It is worth pointing out that Quararibea funebris, Rosita de cacao, a tree which is also sacred, and with remarkable chemicals in its flowers or other parts, is also a member of the Bombacaceae Family. However Rosita de cacao has neither leaves, flowers, nor fruit which look (to a non-botanist) anything like that of Ceiba or Pachira aquatica.

Charles Zidar is a helpful source of information on the Pachira aquatica flower related to Classic Maya art (Zidar and Elisens 2009).

Some specimens may have slight spines but of the seven trees I saw in one area of Guatemala (less than an hour from Monterrico), only one had spines that were large enough to be noticeable and these were only on the lower part of the trunk. There were no large conical spines like on the two common species of ceiba in Guatemala, C. pentandra and C. aesculifolia

Illustrations of the fruit (Parker 2008:103) show pronounced ribs, almost making it look like a cacao pod! But in Guatemala I have never, ever, never seen such ribs. That must be an immature fruit, or a mistake. The surface is smooth when the fruit is mature. The other discrepancy in Parker’s illustration is the size: in reality the fruit is huge, one of the largest tree fruits in all Guatemala.

This species is popular with serious gardeners, especially as a house plant and even for bonsai. Although the natural habitat of this plant is in the humid lowlands, it grows, and flowers, nicely at 1500 meters elevation in Guatemala City, in the Jardin Botanico.

Practical uses, other than symbolic

Several authors mention that the bark produces a red dye. But mostly it is the nuts, leaves, and flowers which are “edible”. However the following article reports that lab rats fed raw Pachira aquatica died within 6 to 8 days.

J. T. A. Oliveira, , I. M. Vasconcelos, L. C. N. M. Bezerra, S. B. Silveira, A. C. O. Monteiro and R. A. Moreira

Composition and nutritional properties of seeds from Pachira aquatica Aubl, Sterculia striata St Hil et Naud and Terminalia catappa Linn. Food Chemistry, Volume 70, Issue 2, 1 August 2000, Pages 185-191.

Common names

Common names are zapote bobo. Pumpo, zapotón

In other parts of Latin America it has completely different local names, such as Provision Tree in English-speaking Belize.

Even to a lay person the leaves look like what you would expect on a Ceiba, but the fruit is huge in comparison to any other ceiba.

amapola, zapote reventon (for Yucatec area of Mexico; comments by David Bolles, linquist)

zapote de agua, apompo (area of Los Tuxtlas; Angeles, Alvarez Guillermo. 1997. Pachira aquatica (apompo, zapote de agua). En: González Soriano Enrique,

Rodolfo Dirzo y Richard C. Vogt. (Editores). Historia Natural de Los Tuxtlas. Instituto de Biología-UNAM/Instituto de Ecología-UNAM/CONABIO. México, D. F. 133-135)

Where we photographed the tree they call it pumpo and also understood the other terms.

atoyaxocotl or fruit of the river could refer to Pachira aquatica Aubl., much used throughout its range as an aromatizer. (Gomez 2008)

Habitat of Pachira aquatica in the Mesoamerican area

I first noticed this tree along the shore of the Rio San Pedro Martyr, Northwestern Peten, Guatemala. In August 2009 we found about seven more of this tree along a lake about 45 minutes drive from the Pacific Coast in Guatemala. It likes to be physically adjacent to water, but is not like a mangrove and can grow away from water (if in a wet area and moist environment). However you may also find this tree in some mangrove areas (along Rio Dulce, Guatemala, for example).

I rarely see this tree along the Arroyo Petexbatun nor Rio de la Pasion, again possibly because during the rainy season anything on the “shore” would be several meters under water.

This tree is not difficult to find if you know what you are looking for, namely the flowers and fruit. If it has no flowers and no fruit, you would need to have memorized the leave pattern to recognize it from afar. However I do not remember very many in the Lake Yaxha (Peten) area. But you can find them along other areas of the country with standing bodies of water. However in some sections of the mangrove swamps none are present (or at least not noticeable). That is probably because those areas flood several meters each rainy season.

There are several Pachira aquatica trees surrounding the main aguada in the Tikal national park (the aguada behind the museum of stelae)

Pachira aquatica Zapoton whole fruit photo studio. FLAAR Photo Archive.

Flowers and fruits of Pachira aquatica

There were flowers and fruits on the Pachira aquatica trees at Tikal during early June. And flowers near the Pacific Ocean in early August. The tree in the Jardin Botanico (far outside its natural range) was flowering healthily during early August.

Pachira aquatica Zapoton peeled fruit photo studio. FLAAR Photo Archive.

Pachira aquatica and leaf-cutting ants

At Tikal the leaf-cutting ants (zompopos) were cutting every fallen flower that they could find. The ants were not climbing into the trees to cut the flowers; the ants simply waited until the flowers fell. The ants cut up almost every single solitary part of the flower.

Related trees (Bombacaceae)

Earlier in my discussion I have already commented on which trees have similar flowers or share other features. Below I list what Levy Tacher et al list as related (2006:83)

- Ceiba pentandra, the normal and common ceiba tree

- Ochroma pyramidale

- Pseudobombax ellipticum

- Quararibea funebris

- Quararibea yunckeri

I can’t further comment because I am in the airport en route to lecture in Johannesburg, so I don’t have Trees of Guatemala with me. But Quararibea yunckeri is not a tree that I am familiar with. Nor with Ochroma pyramidale.

Pachira aquatica Zapoton cut fruit in half photo studio. FLAAR Photo Archive.

Tabulation of indigenous terms for Pachira aquatica In Mesoamerican languages

Very interesting that the tree is called wild cocoa (Guyana), cacao sauvage (Guadeloupe), cacao Cimarron (Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Venezuela),

It turns out this “ceiba” tree is called cacao in many countries of Central and South America (but not in Mexico, Belize, or Guatemala ).

- cacao cimmaron (Nicaragua)

- Cacao de agua (Venezuela)

- Cacao de monte (Columbia, Costa Rica)

- Cacao de playa (Nicaragua)

- Cacao de playa (Nucaragua)

- Cacau-falso, cacau-selvegem, (Brazil)

(Elsevier’s Dictionary of Trees: North America, M. Grandtner, p. 605). Some of these names are also cited much earlier by Pérez 1956.

One reason for calling the tree “cacao” is possibly because the seeds can be ground to make a hot drink with a taste comparable to chocolate but with a bad odor (Janick and Paull p. 182). They say that young leaves and flowers can also be eaten.

Monographs on Pachira aquatica of Mexico, Belize,

Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Costa Rica

- 2007

- Trees in the Life of the Maya World. BRIT PRESS, Botanical Research Institute of Texas. 206 pages.

Regina de Riojas has dedicated much of her life to trees of the Maya and trees of Guatemala. Elfriede de Pöll has likewise dedicated her life, to biology of Guatemala, at Universidad del Valle de Guatemala.

- 2004

- Plants of the Peten Itza’ Maya. Museum of Anthropology, Memoirs, Number 38, University of Michigan. 248 pages.

Very helpful and nice collaboration with local Itza’ Maya people. But would help in the future to have a single index that has all Latin, Spanish, and English plant names so that you can find plants more easily.

Not available as a download.

- 2000

- Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Belize: With Common Names and Uses. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden Vol. 85. 246 pages.

- 2015

- Messages from the Gods: A Guide to the Useful Plants of Belize. The New York Botanical Garden, Oxford University Press.

- 2005

- Biodiversidad del Estado de Tabasco. CONABIO, UNAM, Mexico. 370 pages.

- 2014

- Uso medicinal de plantas antidiabéticas en el legado etnobotánico oaxaqueño. Revista Cubana de Plantas Medicinales 2014;19(1):101-120.

- 2009

- Plantas Comestibles de Centroamérica. Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INBio). Santo Domingo de Heredia. Costa Rica. 360 pages.

Available Online:

www.academia.edu/5891130/Plantas_Comestibles_de_Centroame_rica

Infromation in page 123

- 2016

- The forest of the Lacandon Maya: an ethnobotanical guide. Springer. 334 pages.

Available Online:

www.springer.com/la/book/9781461491101

- 2010

- Prehistoric Human-Environment Interactions in the Southern Maya Lowlands: The Holmul Region Case Final Report to the National Science Foundation.

Figure 21 is a wonderful photograph; first, it is large enough (half page size). Second it is adequately exposed. But most important of all, this helpful photo shows lots of Acoelorrhaphe wrightii around what I estimate is a single Crescentia cujete tree.

Available Online:

www.cich.org/publicaciones/03/INBIO-2009-Plantas-Comestibles-de-CA.pdf

- 2010

- Indicadores ecológicos de la zona riparia del río San Pedro, Tabasco, México. MS Thesis, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. 131 pages.

Available Online:

https://ecosur.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/bitstream/1017/1656/1/100000050585_documento.pdf

- 2000

- Etnobotanica Maya: Origen y evolución de los Huertos Familiares de la Península de Yucatán, México.

Available Online:

www.cich.org/publicaciones/03/INBIO-2009-Plantas-Comestibles-de-CA.pdf

- 2005

- Elsevier’s Dictionary of Trees: North America. Elsevier Science; 1er edición. 1529 pages.

- 2016

- Guía para la identificación de especies de árboles y arbustos comunes en el agropaisaje de Guatemala. 206 pages.

Mentions Pachira aquatica in page 138.

- n.d.

- Flowers of the Maya Art Visible at Tikal: Pachira aquatic, Zapotón. Parque Nacional Tikal Petén. FLAAR Reports.

Available Online:

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.734.2609&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- 2016

- Reproductive biology of Pachira aquatic Aubl. (Malvaceae: Bombacoideae): a tropical tree pollinated bybats, sphingid moths and honey bees. Plant Species Biology 31, 125-134

Available Online:

www.academia.edu/31681233/Reproductive_biology_of_Pachira_aquatica_Aubl._Malvaceae_Bombacoideae_a_tropical_tree_pollinated_by_bats_sphingid_moths_and_honey_bees

- 2014

- ¿Pachira aquatica, un indicador del límite del manglar? Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 85: 143-160

Available Online:

https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S1870345314707407?token=D2A595D63BCEFD8C75820EA0AD163B0BF23A917BDB3DAA5468FF5E76C437AE36E889F8F70461AB397F093A3CE81DDF29

- 2008

- The Encyclopedia of Fruits & Nuts. CABI; First edition. 800 pages.

Note: Even if compiled from other sources it is an excellent compilation on the zapoton tree and fruit

- 2014

- Estructura y composición florística de la vegetación secundaria en tres regiones de la Sierra Norte de Chiapas, México. Polibotánica, No. 37, pp 1-23

Available Online:

www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/polib/n37/n37a1.pdf

- 2011

- Árboles de México. Editorial Trillas. 368 pages.

- 1937

- The Vegetation of Peten. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publ. 478. Washington. 244 pages.

- 1938

- Plants Probably Utilized by the Old Empire Maya of Peten and Adjacent Lowlands. Papers of the Michigan Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters 24, Part I:37-59.

- 2011

- Estado actual y valor de uso etnobotánico de las especies vegetales utilizadas en la industria artesanal alfarera del municipio de Guatajiagua, Morazán El Salvador. Universidad de El Salvador. 54 pages.

Available Online:

http://ri.ues.edu.sv/8952/1/19200931.pdf

- 2003

- Plantas útiles de Peten, Guatemala. Herbario UVAL, Instituto de Investigaciones Universidad del Valle de Guatemala.

- 1987

- Fruits of warm climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami, FL. 550 pages.

- 2018

- Árboles de Calakmul. ECCOSUR, Chiapas. 245 pages.

It is amazing that there is no such book for Parque Nacional Tikal, nor El Mirador. Even though it includes only half the estimated number of “trees,” it has more tree species than Schulze and Whitacre for Tikal (they estimated about 200 but list only about 156 (their lists of species and list by plant family are not identical).

The entire book is a totally free download, however you can’t copy and paste so is difficult to add to your discussion.

Available Online:

http://aleph.ecosur.mx:8991/exlibris/aleph/a22_1/apache_media/74R92GMRSJSEPFDEE5NJY4SJI2I8AK.pdf

- n.d.

- Pachira aquatic Aubl. Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT), Colombia. Manual de Semillas de Arboles Tropicales.

Available Online:

https://rngr.net/publications/manual-de-semillas-de-arboles-tropicales/...ii/.../file

- 2008

- Trees of Guatemala. The Tree Press. 1033 pages.

- 2011

- Árboles del mundo maya. Natural History Museum Publications. 263 pages.

Helpful book; contributing authors are experienced botanists. They cover 220 species of trees, more than virtually all other “Books on Trees of the Maya.” Even include tasiste (which is missing from all other books on “Trees of the Maya” except for the recent book on Árboles de Calakmul.

But if all this effort is going into a book, would help if there were more photos, larger photos, and not so much blank space at the bottom of each page. Plus would help if the text could include personal first hand experience with these trees out in the Mundo Maya. But even as is, it is a helpful book.

If you are doing field work you need this, plus Árboles de Calakmul, plus Árboles tropicales de México. Parker’s book you need back in your office, since out in the field it’s not much help due to lack of photographs. Back in your office the books by Regina Aguirre de Riojas are also helpful.

- 2005

- Árboles tropicales de México. Manual para la identificación de las principals especies. 3rd edition. UNAM, Fondo de Cultura Economica. 523 pages.

This book is a serious botanical monograph. 1968 was the first edition (I still have this), 1998 was second edition. The 3rd edition is a “must have” book. Each tree has an excellent line drawing of leaves and often flowers and fruits (though to understand flowers you need them in photographs, in full color). Each tree has a map showing where found in Mexico (such maps are lacking in most books on Trees of Guatemala or plants of Belize). But trying to fit a description of a tree on one single page means that a lot of potential information on flowering time is not present. Unfortunately, this is definitely not a book on ethnobotany: not one single solitary “use” for Pachira aquatica: for that you need Suzanne Cook.

- 1919

- Batido and other Guatemalan Beverages prepared from Cacao. American Anthropologist, N.S. 21: 403-409.

- 1968

- Brosimum alicastrum as a Subsistence Al¬ternative for the Classic Maya of the Central Southern Lowlands. M.A. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania, University Microfilms, Ann Arbor.

- 1973

- Ancient Maya Settlement Patterns and Environment at Tikal, Guatemala. PhD dissertation, Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania.

Available Online:

www.puleston.org/writings-dissertation.html

But no pagination, and no copy-and-paste facility.

- 2015

- Settlement and Subsistence in Tikal The assembled work of Dennis E. Puleston (Field research 1961-1972). Paris Monographs in America Archaeology 43, BAR International Series 2757. 187 pages.

Available Online:

www.researchgate.net/publication/301202845_Settlement_and_Subsistence_at_

Tikal_The_Assembled_Work_of_Dennis_E_Puleston_Field_research_1961-1972

This is his wife’s reorganization of his 1973 PhD. No tasiste, no nance could I find. Crescentia cujete is only mentioned as a usable plant, seemingly based on Lundell’s 1938 list rather than Puleston finding it in a savanna. In other words, there is no list in this Puleston opus that suggests he studied or made lists of savanna habitats. And there are no photographs of any savanna. Indeed the word savanna is not in his index. This is because the focus of all 1960’s-1970’s Maya field work was in traditional archaeology and in hilltop settlement areas. There were no house mounds in savannas so no interest (in those decades) in studying a savanna.

- 2004

- Estudio morfológico de plántulas de la familia Bombacaceae en Quintana Roo, México. Foresta Veracruzana 6(2):1-6

Available Online:

www.redalyc.org/pdf/497/49760201.pdf

- 2013

- Extracción y caracterización fisicoquímica de aceite fijo obtenido por Expresión de 5 especies nativas y cultivadas en Guatemala: Crescentia cujete (Morro), Mammea americana (Mamey), Pachira aquatica (Zapotón), Cucumis melo (Melón) y Acrocomia mexicana (Coyolio)”. Facultad de Ciencias Quìmicas y Farmacia. Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Guatemala.

Available Online:

http://biblioteca.usac.edu.gt/tesis/06/06_3447.pdf

- 1999

- A Classification and Ordination of the Tree Community of Tikal National Park, Peten, Guatemala. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. Vol. 41, No. 3, pp. 169-297.

Available Online:

www.researchgate.net/publication/291135077_A_classification_and_

ordination_of_the_tree_community_of_Tikal_National_Park_Peten_Guatemala

Even though 20 years ago, it’s the best list of trees of Tikal that I have found. There is a web site with plants of Tikal but they are not separated into trees, vines, shrubs, etc., so harder to use. The new monograph on Arboles de Calakmul is better than anything available so far on Tikal (and the nice albeit short book by Felipe Lanza of decades back on trees of Tikal is neither available as a scanned PDF nor as a book on Amazon or ebay).

- 2000

- A rapid assessment of avifaunal diversity in aquatic habitats of Laguna del Tigre National Park, Petén, Guatemala. In: Bestelmeyer, B.T. and Alonso, L.E. (eds.). A Biological Assessment of Laguna del Tigre National Park, Petén, Guatemala, pp. 56-60. Conservation International.

- 1936

- The Forests and Flora of British Honduras. Field Museum of Natural History. Publication 350, Botanical Series Volume XII. 432 pages plus photographs.

- 1974

- Flora of Guatemala. Fieldiana, Botany, Volume 24, Part X, Number 3.

- 2014

- Characterizing the Chortís Block Biogeographic Province: geological, physiographic, and ecological associations and herpetofaunal diversity, Mesoamerican Herpetology Volume 1, Number 2, December 2014.

- 2011

- Plantas medicinales y comestibles de la Reserva Natural de Usos Multiples Monterrico-RNUMM-, Taxisco, Santa Rosa. Programa Universitario de Investigaciòn en Recursos Naturales y Ambiente- PUIRNA-. Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Guatemala.

Available Online:

http://digi.usac.edu.gt/bvirtual/informes/puirna/INF-2011-024.pdf

- 2002

- Homegardens of Maya Migrants in the District of Palenque (Chiapas/Mexico): Implications for Sustainable Rural Development. In: Stepp, J.R., Wyndham, F.S., and R.K. Zarger (eds.). Ethnobiology and Biocultural Diversity. Pp: 631 – 647. University of Georgia Press; Athens, Georgia

- 1972

- A Highland Maya People and their Habitat: The Natural History, Demography and Economy K´ekchi´ PhD dissertation. 475 pages.

His field work was near San Pedro Carcha, which is now a suburb of Coban, Alta Verapaz. The climate is moist due to moist clouds during many times of the year.

- 2009

- Sacred Giants: Depiction of Bombacoideae on Maya Ceramics in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. Economic Botany, Vol. 63, No. 2, pp. 119-129.

Available Online:

www.researchgate.net/publication/227268745_Sacred_Giants_Depiction_of_

Bombacoideae_n_Maya_Ceramics_in_Mexico_Guatemala_and_Belize

Helpful web sites for any and all plants

There are several web sites that are helpful even though not of a university or botanical garden or government institute.

However most popular web sites are copy-and-paste (a polite way of saying that their authors do not work out in the field, or even in a botanical garden). Many of these web sites are click bait (they make money when you buy stuff in the advertisements that are all along the sides and in wide banners also. So we prefer to focus on web sites that have reliable information.

https://serv.biokic.asu.edu/neotrop/plantae/

Neotropical Flora data base. To start your search click on this page:https://serv.biokic.asu.edu/neotrop/plantae/collections/harvestparams.php

http://legacy.tropicos.org/NameSearch.aspx?projectid=3

This is the main SEARCH page.

https://plantidtools.fieldmuseum.org/pt/rrc/5582

SEARCH page, but only for collection of the Field Museum herbarium, Chicago.

https://fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org/guides?category=37

These field guides are very helpful. Put in the Country (Guatemala) and you get eight photo albums.

http://enciclovida.mx

CONABIO. The video they show on their home page shows a wide range of flowers pollinators, a snake and animals. The videos of the insects are great.

www.kew.org/science/tropamerica/imagedatabase/index.html

Kew gardens in the UK is one of several botanical gardens that I have visited (also New York Botanical Gardens and Missouri Botanical Gardens (MOBOT), in St Louis. Also the botanical garden in Singapore and El Jardín Botánico, the open forest botanical garden in Guatemala City).

www.ThePlantList.org

This is the most reliable botanical web site to find synonyms. In the recent year, only one plant had more synonyms on another botanical web site.

Web sites specifically on Sapotón (Pachira aquatica)

www.backyardnature.net/chiapas/pachira.htm

Information and photos

www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/39234

Information and photos

https://catalogofloravalleaburra.eia.edu.co/species/58

Information and photos

www.monaconatureencyclopedia.com/pachira-aquatica/?lang=es

Information

www.naturalista.mx/taxa/154852-Pachira-aquatica

Photos and map distribution

http://www.tramil.net/es/plant/pachira-aquatica

Photos

Last update May, 2020.

First posted August 2011.

Updated by Vivian Hurtado, manager of bibliography preparation, FLAAR Mesoamerica.