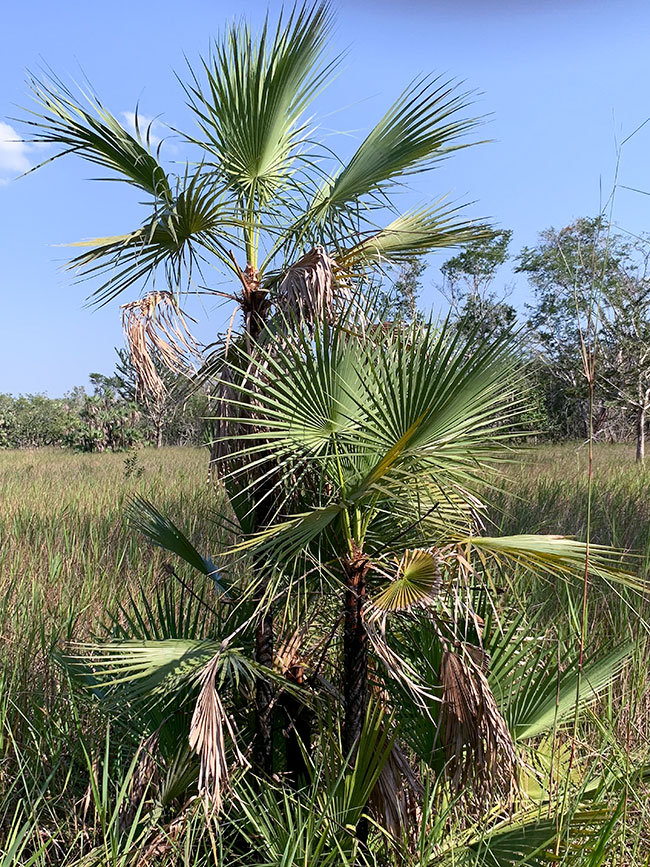

Acoelorrhaphe wrightii, palmetto palm, in Peten, only found in savannas

When we finally reached the savanna east of Nakum (Peten, Guatemala) we were amazed to see a species of palm I have never previously found anywhere at Yaxha, Nakum, or Naranjo areas of this large national park. Surely this palm will be found elsewhere in the park but for now this is a great find. We are checking to see what savannas exist in or physically adjacent to the outside of the nearby Tikal park (because if there are savannas inside or estimating that the pine trees at northeast (just outside) then there surely will be Acoelorrhaphe wrightii there also. This is because pine trees occur in this part of Peten almost only in a grassland savanna; and the same savannas almost always have Acoelorrhaphe wrightii, palmetto palm.

But in the meantime, we are very happy to have found the palmetto palm in Parque Nacional Yaxha Nakum Naranjo. It was a rough hike, with the final several hundred meters trying not to fall down the steep fractured edge of an unexpected deep geological fault line (on the hill directly at the edge of the flat savanna).

I found this savanna on the aerial maps of Instituto Geografico Nacional (Guatemala). We will be publishing reports on everything our team has discovered on the initial visit plus what we find when we return.

Acoelorrhaphe wrightti Palmetto palm at Savanna, Nakum-Yaxha Park, Peten. Photo by Dr. Nicholas Hellmuth using an iPhone Xs

Many different names for most plants

Lots of names for most plants of Mesoamerica: depends whether you are in Florida, Silver saw palm, or Guatemala, palmetto palm. Other names include paurotis palm. Local names also depend what part of Mesoamerica you are in: tasisté is one. Té or ché both mean tree (in most Mayan languages).

Somewhere I thought I saw Pimento palm as a name for Acoelorrhaphe wrightii but when you Google Pimento palm you get the Genus species name Schippia concolor. So I went elsewhere to look and found that botanist Harley Harris Bartlett uses the name (but spelled pimenta, not pimiento) pimenta palm for Acoelorraphe pinetorum (1935: caption to Plate 2 and to Plate 2). The concept of pine area as species name is probably meaning palm tree near pine trees??). Acoelorraphe pinetorum is the old name of the 1930’s; most of these palm trees are near pine trees in Belize.

Bartlett spells the genus Acoeloraphe; the correct spelling that Google wants to see is Acoelorrhaphe. Yet both spellings are found in older books. And www.ThePlantList.org of course tells you clearly that the correct botanical name today is Acoelorrhaphe wrightii (Griseb. & H.Wendl.) H.Wendl. ex Becc. A dozen other plant names are synonyms (www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/record/kew-2153).

We would not recommend using the word pimenta palm because you either get allspice tree or a hot chile pepper in Google returns. Palmetto is a better word. Or Silver Saw palmetto (www.palmworld.org/view_object.php?p=MjQ4)

Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palm, is any part edible?

Most palms of the Mayan areas have one or more edible parts. We will do more research to learn whether the ancient Mayan people of Nakum could have, or would have, eaten part of this palm.

Another medicinal plant of the Maya: Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palm

For thousands of years thousands of Mayan people lived in the Nakum area so now we can add another medicinal plant for them.

We estimate there are between 500 and 600+ medicinal plants used in the Mayan areas of Mesoamerica. Several hundred are still used today, but every year fewer are utilized, as the grandmothers and grandfathers are the primary individuals who know which plant for which illness or skin condition.

Some of these plants could provide medicine to cure serious diseases. We have been working on making our list of medicinal plants and as soon as realistic funding available we can have not only a list, but also a complete bibliography about what lab experiments have already been accomplished, plant by plant, around the world.

Most of the initial medicines of Europe are from medicinal plants of the Greeks, Romans, and Arabs. Obviously the original medicine of India, China, and most other countries was primarily plant-based.

Additional uses of Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palm

As is typical of many palm trees of the Maya areas, Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palm can be used for house construction. Plus you can make various products. But since there are so many other palms more common in Guatemala, you will unlikely find this particular plant used locally for roof thatch or for handicrafts. But in Belize this tree is growing close to towns, villages, and cities, so it is more likely used still today.

Where can you find Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palm?

Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palm is found in Lacandon areas of Chiapas (Cook 2016: 117) and in many other parts of Mesoamerica. We are still working on a bibliography (plant by plant, and ecosystem type by ecosystem type; FLAAR Mesoamerica has an experienced team of researchers).

This Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palm grows here in the savanna east of Nakum because it has evolved the ability to survive soil that is seasonally wet or occasionally flooded. They like full total sun: all the palmetto palm trees that we saw were in the middle of the savanna, not at the far edges. But since there is so much sun in this part of the world, I would not be surprised to find some Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palms on the edges of the savanna also, in the occasionally shade of a Haematoxylum campechianum tree (which are scattered throughout the southern part of the bajo; we have not yet explored the central or northern part).

We will also check if Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palm grow in the shade of the Crescentia cujete trees. These calabash trees are the most obvious trees in the entire savanna, along with all the beautiful clumps of Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palm.

Acoelorrhaphe wrightti Palmetto palm at Savanna, Nakum-Yaxha Park, Peten. Photo by Dr. Nicholas Hellmuth using an iPhone Xs.

Where can you find Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palm?

Since is native to Florida, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean islands, it has evolved to survive in various diverse ecosystems (as long as water is available during its growth and occasionally a lot when grown).

There is no salt that we know of in the soils of Yaxha aguadas since this area is far far from the Caribbean coast and far from Salinas de los Nueve Cerros (an area of black salt to the western part of Peten).

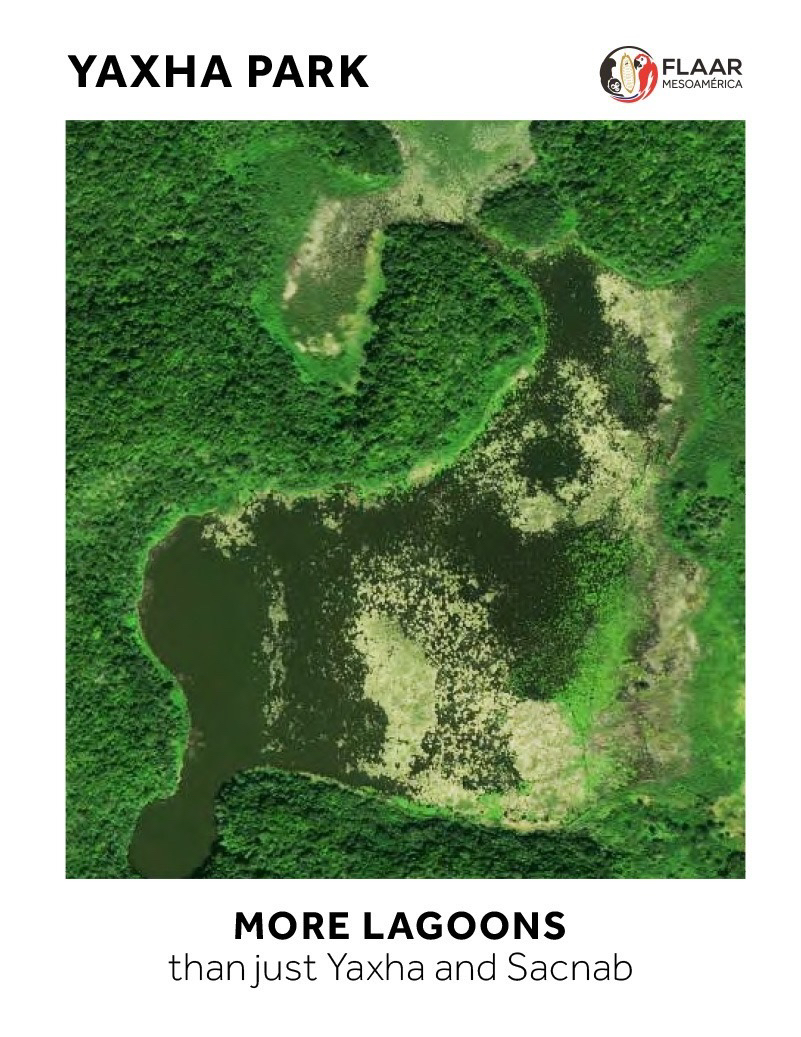

The savanna near Laguna Yaloch is near the same Rio Holmul which is not far from the savanna east of Nakum where we found Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palms. The diversity of ecosystems parallel to the curling path of the Rio Holmul and its branches is impressive: mostly bajo with thick entangled vegetation, but also the savanna of impressive size near Nakum.

We do not have all the aerial photos of the entire path of the Rio Holmul from Tikal area or the Rio Holmul northeast of Naranjo (majestic ancient Mayan city in the Yaxha Nakum Naranjo park) to the Belize border, but it would be worth searching the western area of the Rio Holmul to see if more savannas are to be found there.

Acoelorrhaphe wrightii is drought tolerant since many years the savannas get no rain

August through December 2018 and January-February 2019 were among the driest months that I can remember for this part of Peten. It rained only once or twice some of these months; or at most once a week in the wettest of this unexpected dry wet season.

Yet all the Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palm in the savanna seemed healthy and happy when we found them in February. This may be because the savanna soil may have access to water dripping down from the nearby hills (long after it rains). Or the soil simply may be able to store some wetness for a while.

Most savannas are burned by local people

Local hunters like to get rid of the grass so they can see the game animals (so they can shoot them). So we are told that most savannas (and possible sibal areas also) are burned every year. We were thus lucky to see the grass at its natural knee-height for the savanna. It is helpful to protect the vegetation to protect the wild animals.

Acoelorrhaphe wrightii trunks can be reddish tint

I was pleasantly surprised to see a red color on part of the trunk of these palmetto palm trees. Thus these palms can make a great garden plant. But do not take them from any wild forest. Try to find seeds or find them in a plant nursery.

Acoelorrhaphe wrightii grows in clumps (clusters)

Guano palms grow “hundreds in one ecosystem” but each tree is separate from all the others (even if entangled because of the thickness of the bajo or hillside forest vegetation). Same with corozo (cohune) palm trees: could be close to a thousand individual trees in the dense areas where they are 90% of the vegetation: called corozal or corozera (singular for the area, since it is one area that gets the name for the hundreds that are near each other).

But Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palms, in this savanna, always grow in a clump. However I estimate that each tree is an individual (even if it happens to bump into another one nearby). Same with corozo palms: hundreds or thousands within a square kilometer in “corozals” or “corozeras.” But each tree is independent even if growing next to another. But neither guano nor corozo nor escobo palms grow in the same kind of almost conjoined clumps as do the Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palms.

With Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palms, they grow in clusters. I did not notice any single individual independent trees (though I would not be surprised to find a single tree, where the others have died or been chopped down or otherwise destroyed).

Bactris species of palms has many local names, Huiscoyol is one. These dense stands are typical of how this spiny palm tree grows along the Rio Icbolay.

Photographed by Dr. Nicholas on May 31,2018 with a Nikon D810, Lens Canon EF 300mm f/2.8L IS II USM, f/8 y 1/250 ISO 1250.

Photographed by Melanny Quiñonez on May 31,2018 with a Canon, Lens AF-S VR Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/2.8G IF-ED, f/4 y 1/80 ISO 4000.

Huiscoyol (Bactris species) also grow in clumps: with so many thousands of needle-thin and full length spines that you have to be very careful). But so far there are not enough Bactris palms found in the park area to see whether they grow in clumps (as they do along rivers). We found dense clumps of Bactris palms several meters away from dense clumps of Guadua bamboo along the Rio Icbolay, east of Parque Lachua, Guatemala. Rio Icbolay is a tributary of the Rio Chixoy. All this is in the area where southwestern part of Peten borders on northwestern part of Alta Verapaz.

Spiny bamboo, growing in clumps along the Rio Icbolay.

Photographed by Melanny Quiñoñez with a CANON EOS 6D, lens AF-S VR Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/2.8G IF-ED, f/5.6, 1/640, ISO200 on May 31, 2018.

One of our plant scouts lives on the Rio Icbolay, so that’s how we got to see, experience, and photograph the Bactris and Guadua bamboo along this totally non-touristed river.

The Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palms are not very high, some are up to 5 meters, I doubt higher than 6 or 7 meters. We would need to physically measure them to comment further. Obviously lots of younger trees, so not as tall as the older ones.

Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palms grow near Crescentia cujete (calabash trees)

In a moist savanna near Laguna Yaloch in the Holmul area of northeastern Peten the researchers found Acoelorrhaphe wrightii palms in same grassland as Crescentia cujete, guarumo, and Ceiba. But as we will discuss in the eventual full report (in .PDF format), guarumo and Ceiba “grow everywhere” so are not in any way whatsoever indicative of a savanna ecosystem. But the savanna east of Nakum is the first place that we found Crescentia cujete growing wild in Parque Nacional Yaxha Nakum Naranjo. So Crescentia cujete is definitely a savanna indicator (in this part of Guatemala; of course jicara and especially morro trees are planted around Mayan houses to supply containers to drink cacao and for their seeds).

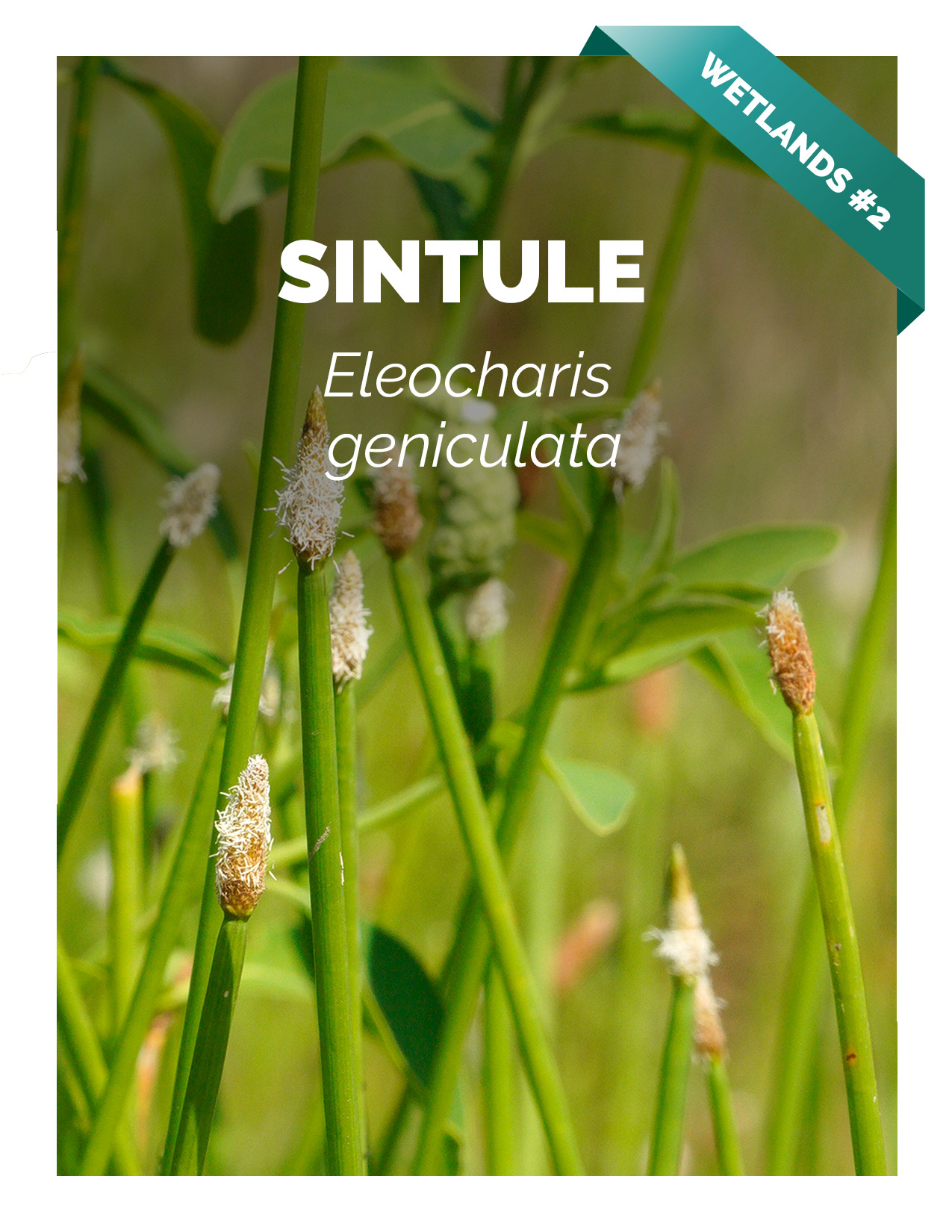

The savanna near Laguna Yaloch also had ferns, Eleocharis sp (polol) and aster (Wahl, Estrada-Belli and Anderson 2013). We had only a single hour to spend in the Nakum savanna since there was no known trail here and our helpful guides thus had to hike in every direction to figure out how to find the savanna. Then it turned out that there was an enormous geological fault line on a steep hill overlooking the north side of the savanna. It took a while to figure out how to find a way to hike down this hill without falling into the abyss or sliding on the dry leaves which cover the forest soil. And, once we got to the savanna, we had to figure out how to climb the fault line to get to the top of the hill so we could hike the several hours back to the camp area at Nakum.

Savanna Ecosystem features Acoelorrhaphe wrightii, palmetto palm

Everything noted in savannas of Peten and Belize (not always correctly; so I do not associate Ceiba or Cecropia with a savanna; they are “everywhere” in a dozen eco-systems.

| Common names | Which have we found so far in the savanna east of Nakum | Uses, and comments |

|---|

| Acoelorrhaphe wrightii | Palmetto palm | Acoelorrhaphe wrightii | Medicinal, construction |

| Bucida buceras | Bullet tree, pucte | ||

| Byrsonimia crassifolia | Nance, craboo | Edible fruit | |

| Crescentia cujete | Calabash tree, jicaro; relative of Crescentia alata. | Crescentia cujete | Very useful to make cups, musical instruments |

| Curatella americana | Sandpaper tree, haha, chapparo | Sandpaper leaves; also flavoring for cacao drink | |

| Eleocharis sp, polol | Many grasses are usable for baskets and comparable woven products | ||

| Ferns (no genus suggested) | (Wahl, Estrada-Belli and Anderson 2013). (Estrada-Belli and Wahl 2010: 7). | There are so many tiny ferns no way to know even genus; for giant ferns, we found incredible forest in Aguada Maya near Poza Maya (between Yaxha and Nakum). | |

| Aster | (Estrada-Belli and Wahl 2010: 7). | Maybe Viguiera sp.? | |

| Pinus caribaea | Local pine tree | So far not one single pine in Yaxha area | |

| Quercus oleoides | Oak tree | Oak would not surprise me, but not yet documented for Yaxha. |

Haematoxylum campechianum, palo de tinto, palo de Campeche, logwood, is a tree of bajos; not of savannas; but since many savannas merge into a bajo, you can find Haematoxylum campechianum trees along the edge(s) of a savanna (as we found at the savanna east of Nakum). But I do not include palo de tinto as “a tree of the savannas.”

To learn more about aster in Peten, would need to do considerable research in works by Blake over a century ago. The PhD dissertation of Akpinar (2011: 85) mentions an aster seed for Peten.

If you look at savannas in other parts of Mexico or other parts of Mesoamerica you will understandably find additional plants listed. Often that is because the soils and seasonal climate is not the same as Peten or Belize. But, nonetheless, it always helps to know what plants to look for in a Peten savanna because unless you are looking for it, in the mass of entangled plants you might never notice it. For example, we should look for:

Cladium jamaicense, sawgrass, more a feature of a sibal (cibal, cival).

Coccoloba barbadensis, uvero

Palm by Palm, making list of all palm trees of the Yaxha Park

Our major goal is to make a list of all trees of Yaxha. We estimate, based on lists of nearby areas of Guatemala, that about 200 species of trees are present. Obviously we also wish to make a list of all other plants, but with over 1800 species of other plants (not counting mushrooms and lichens and other thing which are “not plants”). Field trip costs, staff, research team, getting back and forth, operating overhead, books we need to buy, camera equipment average about one thousand dollars a tree (the field work cost is over $20K a month since the staff work all month doing the research and then identifying everything photographed during each monthly field trip of about a week). There is not (yet) enough Internet strength of solar energy to charge our camera batteries and computers (yes, we have portable batteries; yes we have solar panels at the camp: but we have sophisticated digital camera equipment of a level most projects are not familiar with, since FLAAR has focused on digital photography technology trends for over 25 years).

So as soon as a kind, considerate, and helpful individual, foundation, university, of other entity can provide funds for the remaining 100 trees and remaining 1700 plants, we are doing the best we can: to our knowledge we are the first project to document and photograph the savanna east of Nakum.

Corozo palm, guano palm, escoba palm, bayal palm and three species of xate palm are obviously present (everywhere except in the savanna). Huiscoyol (Bactris species) are very common along rivers elsewhere in Peten, but unexpected rare in the Yaxha-Nakum part of the park we had to accomplish many field trips before we found any. Now we have between 9 and 12 more palms to find.

Introductory Bibliography on Acoelorrhaphe wrightii, palmetto palm

With 200 trees and 1800 plants, it takes a while to do each needed bibliography. But here are a few titles.

- 2007

- Trees in the Life of the Maya World. BRIT PRESS, Botanical Research Institute of Texas. 206 pages.

Regina de Riojas has dedicated much of her life to trees of the Maya and trees of Guatemala. Elfriede de Pöll has likewise dedicated her life, to biology of Guatemala, at Universidad del Valle de Guatemala.

Sold on Sophos:

https://tienda.sophosenlinea.com/libro/trees-in-the-life-of-the-maya-world_41562

- 2012

- Palm species richness, abundance and diversity in the Yucatan Peninsula, in a neotropical context. Nordic Journal of Botany 30. Pages 1-10

Available online:

www.researchgate.net/publication/264477246_Palm_species_richness_abundance_and_diversity_in_the_Yucatan_Peninsula_in_a_neotropical_context

- 2004

- Plants of the Peten Itza’ Maya. Museum of Anthropology, Memoirs, Number 38, University of Michigan. 248 pages.

Very helpful and nice collaboration with local Itza’ Maya people. But would help in the future to have a single index that has all Latin, Spanish, and English plant names so that you can find plants more easily.

After searching page by page in plant family ARECACEAE, found Acoelorrhaphe wrightii on top left of page 153: helpful list of uses that are not in most other botanical monographs nor articles.

Not available as a download, so all the more difficult to search (since searching on your computer is the most effective way to initiate botanical research nowadays; this is why our team dedicated several months to scanning Lundell’s monograph (since the CIW kindly had no copyright, precisely to help share their non-profit research publications).

- 1940

- Several palm problems. 33. Acoelorraphe vs. Paurotis. Silver Saw Palms. Gentes Herbarum 4: 361-365.

- 1994

- The Conservation Status of Schippia concolor in Belize. Principes, 38(3), pp. 124-128.

Available online:

www.nybg.org/files/scientists/mbalick/The%20Conservation%20Status%20of%20Schippia%20concolor%20in%20Belize.pdf

- 2000

- Acoelorrhaphe wrightii is listed on page 194.

- 2000

- Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Belize: With Common Names and Uses. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden Vol. 85. 246 pages.

Sold online:

www.amazon.com/Checklist-Vascular-Plants-Belize-Botanical/dp/0893274402

- 2015

- Messages from the Gods: A Guide to the Useful Plants of Belize. The New York Botanical Garden, Oxford University Press.

Sold online:

www.amazon.com/-/es/Michael-J-Balick/dp/0199965765

- 1958

- Breeding biology of Jabirus (Jabiru mycteria) in Belize. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 117(2), 142-153. 2005.

Full-text available:

www.researchgate.net/publication/240776582_Breeding_biology_of_Jabirus_Jabiru_mycteria_in_Belize

- 2005

- Biodiversidad del Estado de Tabasco. CONABIO, UNAM, Mexico. 370 pages.

- 2007

- Guía Ilustrada de las Plantas del Petén y sus Usos. Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan.

Available online:

https://idoc.pub/download/guia-ilustrada-de-las-plantas-del-peten-yucatan-8x4eok88m3n3

- 2008

- Adaptación ante disturbios naturales, manglar de Puerto Morelos, Quintana Roo, México. Foresta Veracruzana.

Available online:

www.redalyc.org/pdf/497/49711434004.pdf

- 2003

- Plan Maestro del Parque Nacional Tikal 2003-2008. Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes-Dirección del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural-Parque Nacional Tikal. The Nature Conservancy, RARE, WCS, UNESCO and USAID. 135 pages.

Available online:

www.conservationgateway.org/Documents/10.Plan%20Maestro%20Tikal%20FINAL.pdf

- 2007

- Casa, madera y simbiosis arquitectónica en Belize y el Suereste de México. Departamento de Geografía, Universidad de Quintana Roo, México. Gazeta de Antropología. No 23, Art. 7

Available online:

www.researchgate.net/profile/Martin_CHECA_ARTASU/publication/28154203_Casa_madera_y_simbiosis_arquitectonica_en_Belice_y_el_sureste_de_Mexico/links/0fcfd51395723cb737000000/Casa-madera-y-simbiosis-arquitectonica-en-Belice-y-el-sureste-de-Mexico.pdf

- 2016

- Centroamérica Patrimonio Vivo: Reflexiones en torno a la arquitectura histórica en madera de Belice.

Available online:

https://rio.upo.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10433/5050/Checa-Artasu%2c%20Mart%c3%adn%20M..pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y

Note: information about the architectonic uses of tasiste on pages 30-32

- 2016

- The forest of the Lacandon Maya: an ethnobotanical guide. Springer. 334 pages.

Sold online:

www.springer.com/la/book/9781461491101

- 2006

- Plan Maestro del Parque Nacional Yaxha – Nakum – Naranjo 2006-2010. 168 pages.

Available online:

https://issuu.com/informaticapatrimonio/docs/plan_maestro_yaxha_nakun-naranjo\

- 2015

- Plan Maestro del Parque Nacional Yaxha, Nakum, Naranjo, primera actualización. CONAP. 335 pages.

Available online:

https://conap.gob.gt/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/PM-PN-Yaxha-Nakum-Naranjo.pdf

- 2017

- Morphology, Architecture and Growth of a Clonal Palm, Acoelorrhaphe wrightii. Florida International University FIU Digital Commons. 172 pages

Available online:

https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4180&context=etd#page=132

- 2010

- Prehistoric Human-Environment Interactions in the Southern Maya Lowlands: The Holmul Region Case Final Report to the National Science Foundation.

Figure 21 is a wonderful photograph; first, it is large enough (half page size). Second it is adequately exposed. But most important of all, this helpful photo shows lots of Acoelorrhaphe wrightii around what I estimate is a single Crescentia cujete tree. What is notable is that these palms are NOT in clumps: there are lots of them; they are near each other, but none have their trunks touching each other (their leaves, yes, but not their trunks).

The caption of this photograph (captions are not under the illustrations but are in order before the illustrations start): 21. Fire scarring of woody taxa (Crescentia cujete and Acoelorrhaphe wrightii shown here) on the periphery of the wetland surrounding Laguna Yaloch (no page numbers in this part of the report).

So this helpful field work is further documentation that Acoelorrhaphe wrightii prospers in wetlands. Thus it was sheer luck that April through December 2018 and January-February of 2019 were so dry that we could drive to Nakum in August through December (almost every month but one) and both January and February (though our 4WD pickup trunk was rented, so it was not fully equipable for deep-rut roads like this route; this route is destroyed by sports-4WD macho-vehicles whose wide and excessively high tires leave deep deep ruts.

- 2010

- Indicadores ecológicos de la zona riparia del río San Pedro, Tabasco, México. MS Thesis, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. 131 pages.

Available online:

https://ecosur.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/bitstream/1017/1656/1/

100000050585_documento.pdf

- 2001

- Investigaciones arqueológicas en el Bajo Santa Fe y la Cuenca del Río Holmul, Petén: Parte 2. Región Noreste del Parque Nacional Tikal y Periferia de Nakum. Temporada 2001. Proyecto Nacional Tikal. Sub-Proyecto Triángulo Yaxhá-Nakum-Naranjo. Instituto de Antropología e Historia. Guatemala.

- 2000

- Etnobotanica Maya: Origen y evolución de los Huertos Familiares de la Península de Yucatán, México.

Available online:

https://helvia.uco.es/bitstream/handle/10396/339/13207854.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 2014

- Estudio etnobotánico y taxonómicao dela familia Arecaceae, en el municipio de Macuspana. Tabasco, México. Universidad Juarez Autonoma de Tabasco. Thesis. 395 pages.

Available online:

https://revistas.ujat.mx/index.php/kuxulkab/article/view/2621

- 1997

- Field Guide to the Palms of the Americas, Princeton University Press. 363 pages. Some web sites list the date as 1995; most list the date as 2019.

Sold online:

www.amazon.com/-/es/Andrew-Henderson/dp/0691016003

- 2011

- Árboles de México. Editorial Trillas. 368 pages.

- n.d.

- Flora and vegetation of freshwater wetlands in the coastal zone of the gulf of mexico. pp. 314-339.

Available online:

www.harteresearchinstitute.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/16.pdf

- 1937

- The Vegetation of Peten. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publ. 478. Washington. 244 pages.

Neither Acoelorrhaphe wrightii nor synonym Paurotis wrightii nor any other Paurotis is in his index.

- 1938

- Plants Probably Utilized by the Old Empire Maya of Peten and Adjacent Lowlands. Papers of the Michigan Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters 24, Part I:37-59.

- 1969

- Plantae Mayanae II. Collections from Peten and Belice. Wrightia 2(3): 111- 126.

After botanist Cyrus Lundell worked in the La Libertad area of Peten and published his findings in 1937 and 1938, he moved elsewhere. And then decades later he worked for botanical entities in USA. All his 1930’s research is published in a single monograph, The Vegetation of Peten. But all his 1940’s-1960’s botanical field work is scattered and splattered. It would be a monumental contribution to the botanical knowledge of the Mayan areas if all his botanical research for Peten and adjacent Belize could be scanned and turned into a single e-resource. Crucial is to have this research copy-and-pastable (so you can cite it in your own research). Crucial also is to have the scans spelling corrected. Our team at FLAAR Mesoamerica dedicated several weeks to scanning every page of The Vegetation of Peten and two months to spell-checking and hand-correcting every word. But we do not have access to the original articles of Lundell of the 1940’s, 1950’s, 1960’s, etc. Our scan of The Vegetation of Peten will be made available in May 2020 on our www.maya-ethnobotany.org at no cost to botanists, students, research entities and the interested public.

- 2017

- Estudio taxonómico de la familia Arecaceae en el municipio de Macuspana,

Tabasco, México. Kuxulkab’-Tierra viva o naturaleza en voz chontal. Vol. 23, no. 47, pp. 5-15. universidad juarez autonoma de tabasco, division académica de ciencias biológicas 2017.

Downloadable on the Internet courtesy of the university:

www.revistas.ujat.mx/index.php/kuxulkab/article/view/2621

- 2011

- Estado actual y valor de uso etnobotánico de las especies vegetales utilizadas en la industria artesanal alfarera del municipio de Guatajiagua, Morazán El Salvador. Universidad de El Salvador. 54 pages.

Available online:

http://ri.ues.edu.sv/id/eprint/8952/1/19200931.pdf

- 2019

- A Review of the Nomenclature and Types of the Genus Acoelorraphe (Arecaceae). PalmArbor 2019-3: 1-30.

Available online:

www.researchgate.net/profile/Celio-Moya/publication/338545020_A_Review_of_the_Nomenclature_and_Types_of_the_Genus_Acoelorraphe_Arecaceae_Una_Revision_de_la_Nomenclatura_y_los_Tipos_del_Genero_Acoelorraphe_Arecaceae/links/5e1b8b0592851c8364c8d80c/A-Review-of-the-Nomenclature-and-Types-of-the-Genus-Acoelorraphe-Arecaceae-Una-Revision-de-la-Nomenclatura-y-los-Tipos-del-Genero-Acoelorraphe-Arecaceae.pdf

- 2018

- Árboles de Calakmul. ECCOSUR, Chiapas. 245 pages.

It is amazing that there is no such book for Parque Nacional Tikal, nor El Mirador. Even though it includes only half the estimated number of “trees,” it has more tree species than Schulze and Whitacre for Tikal (they estimated about 200 but list only about 156 (their lists of species and list by plant family are not identical).

The entire book is a totally free download, however you can’t copy and paste so is difficult to add to your discussion.

Available online:

http://aleph.ecosur.mx:8991/exlibris/aleph/a22_1/apache_media/74R92GMRSJSEPFDEE5NJY4SJI2I8AK.pdf

- 2008

- Trees of Guatemala. The Tree Press. 1033 pages.

- 2005

- Árboles tropicales de México. Manual para la identificación de las principals especies. 3rd edition. UNAM, Fondo de Cultura Economica. 523 pages.

This book is a serious botanical monograph. 1968 was the first edition (I still have this), 1998 was second edition. The 3rd edition is a “must have” book. Each tree has an excellent line drawing of leaves and often flowers and fruits (though to understand flowers you need them in photographs, in full color). Each tree has a map showing where found in Mexico (such maps are lacking in most books on Trees of Guatemala or plants of Belize). But trying to fit a description of a tree on one single page means that a lot of potential information on flowering time is not present. And, this is definitely not a book on ethnobotany: for that you need Suzanne Cook.

- 2011

- Árboles del mundo maya. Natural History Museum Publications. 263 pages.

Helpful book; contributing authors are experienced botanists. They cover 220 species of trees, more than virtually all other “Books on Trees of the Maya.” Even include tasiste (which is missing from all other books on “Trees of the Maya” except for the recent book on Árboles de Calakmul).

But if all this effort is going into a book, would help if there were more photos, larger photos, and not so much blank space at the bottom of each page. Plus would help if the text could include personal first hand experience with these trees out in the Mundo Maya. But even as is, it is a helpful book.

If you are doing field work you need this, plus Árboles de Calakmul, plus Árboles tropicales de México (though tasiste is conspicuously missing). Parker’s book you need back in your office, since out in the field it’s not much help due to lack of photographs. Back in your office the books by Regina Aguirre de Riojas are also very helpful.

- 1973

- Ancient Maya Settlement Patterns and Environment at Tikal,

Guatemala. PhD dissertation, Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania.

Available online:

www.puleston.org/writings-dissertation.html

But no pagination, and no copy-and-paste facility.

- 2015

- Settlement and Subsistence in Tikal The assembled work of Dennis E. Puleston (Field research 1961-1972). Paris Monographs in America Archaeology 43, BAR International Series 2757. 187 pages.

This is his wife’s reorganization of his 1973 PhD. No tasiste, no nance could I find. Crescentia cujete is only mentioned as a usable plant, seemingly based on Lundell’s 1938 list rather than Puleston finding it in a savanna. In other words, there is no list in this Puleston opus that suggests he studied or made lists of savanna habitats. And there are no photographs of any savanna. Indeed the word savanna is not in his index. This is because the focus of all 1960’s-1970’s Maya field work was in traditional archaeology and in hilltop settlement areas. There were no house mounds in savannas so no interest (in those decades) in studying a savanna.

- 2004

- Arecaceae de la Península de Yucatán. Etnoflora Yucatense, Fas. 23. Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán.

- 2018

- Germination and juvenile growth of the clonal palm, Acoelorrhaphe wrightii, under different water and light treatments: a mesocosm study. Florida International University, Department of Biological Sciences and International Center for Tropical Botany. Feddes Repertorium No. 129. Pages 92–104

Available online:

www.researchgate.net/publication/325560109_Germination_and_juvenile_

growth_of_the_clonal_palm_Acoelorrhaphe_wrightii_under_different_water_

and_light_treatments_a_mesocosm_study

- 1999

- A Classification and Ordination of the Tree Community of Tikal National Park, Peten, Guatemala. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. Vol. 41, No. 3, pp. 169-297.

Even though 20 years ago, it’s the best list of trees of Tikal that I have found. There is a web site with plants of Tikal but they are not separated into trees, vines, shrubs, etc., so harder to use. The new monograph on Arboles de Calakmul is better than anything available so far on Tikal (and the nice albeit short book by Felipe Lanza of decades back on trees of Tikal is neither available as a scanned PDF nor as a book on Amazon or ebay).

Available online:

www.researchgate.net/publication/291135077_A_classification_and_ordination_of_the_tree_community_of_Tikal_National_Park_Peten_Guatemala

- 2000

- A rapid assessment of avifaunal diversity in aquatic habitats of Laguna del Tigre National Park, Petén, Guatemala. In: Bestelmeyer, B.T. and Alonso, L.E. (eds.). A Biological Assessment of Laguna del Tigre National Park, Petén, Guatemala, pp. 56-60. Conservation International.

Available online:

www.academia.edu/1347846/A_Biological_Assessment_of_Laguna_del_Tigre_National_Park_Pet%C3%A9n_Guatemala

- 1922

- The saw-cabbage palm. The history and distribution of Paurotis wrightii. J. New York Bot. Gard. 23: 61-70.

- 1936

- The Forests and Flora of British Honduras. Field Museum of Natural History. Publication 350, Botanical Series Volume XII. 432 pages plus photographs.

- 1958

- Flora of Guatemala. Fieldiana: Botany, Volume 24, art I. Chicago Natural History Museum.

Free download from various web sites. But some versions are easier to copy-and-paste than other versions. All have spelling errors when any Spanish or Mayan word has an accent.

- 2005

- Conocimiento ecológico y sistema de manejo maya del lagarto (Crocodylus moreletii) en Quintana Roo, México. Thesis.

Available online:

http://aleph.ecosur.mx:8991/exlibris/aleph/a22_1/apache_media/LP95GN64F2PFAJL5CT1MV251BHNSNS.pdf

- 2013

- Maíz, clima y fuego en la región de Holmul, Petén, Guatemala. En XXVI Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2012 (editado por B. Arroyo y L. Méndez Salinas), pp. 611-621. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala.

Available online:

www.asociaciontikal.com/simposio-26-ano-2012-2/049-maiz-clima-y-fuego-en-la-region-de-holmul-peten-guatemala-david-b-wahl-francisco-estrada-belli-y-lysanna-anderson-simposio-26-2012/

Acoelorrhaphe wrightii (Griseb. & H.Wendl.) H.Wendl. ex Becc.

Guatemala, Petén, Rio Pucte, on river bank

Guatemala, Petén, Sayaxche, Rio Pucte camp, in tintal, 1 km. south of the camp, 200m east of the river

Guatemala, Petén, El Ceibo, bordering Rio San Pedro, about 500m of the village

Guatemala, Petén, Tikal National Park, 46 km, on Brecha (J) Petrolera -- pinal Bajo de Santa Fe

Helpful web sites for any and all plants

There are several web sites that are helpful even though not of a university or botanical garden or government institute.

However most popular web sites are copy-and-paste (a polite way of saying that their authors do not work out in the field, or even in a botanical garden). Many of these web sites are click bait (they make money when you buy stuff in the advertisements that are all along the sides and in wide banners also. So we prefer to focus on web sites that have reliable information.

https://serv.biokic.asu.edu/neotrop/plantae/

Neotropical Flora data base. To start your search click on this page:

https://serv.biokic.asu.edu/neotrop/plantae/collections/harvestparams.php

http://enciclovida.mx

CONABIO. The video they show on their home page shows a wide range of flowers pollinators, a snake and animals. The videos of the insects are great.

www.kew.org/science/tropamerica/imagedatabase/index.html

Kew gardens in the UK is one of several botanical gardens that I have visited (also New York Botanical Gardens and Missouri Botanical Gardens (MOBOT), in St Louis. Also the botanical garden in Singapore and El Jardín Botánico, the open forest botanical garden in Guatemala City).

www.ThePlantList.org

This is the most reliable botanical web site to find synonyms. In the recent year, only one plant had more synonyms on another botanical web site.

Web sites specifically on Acoelorrhaphe wrightii

https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/st058

University of Florida, on why fronds are often yellow color.

www.maya-ethnobotany.org/mayan-ecosystems-chiapas-peten-belize/acoelorrhaphe-wrightii-palmetto-palm-mayan-savanna-ecosystem-hellmuth-flaar-nakum-peten.php

Tasiste palm discovered near Crescentia cujete trees in Savanna East of Nakum, PNYNN.

www.palmworld.org/view_object.php?p=MjQ4

Helpful introduction.

http://sds.yucatan.gob.mx/flora/fichas-tecnicas/Tasiste.pdf

One small photo; one short page.

Updated July, 2021 by Vivian Hurtado, FLAAR Mesoamerica

First posted March, 2019